Why have Venice, Italy and the world’s media been stunned by corruption arrests linked to Venice’s MoSE dams and the resignation of Venice Mayor Orsoni?

Giorgio Orsoni resigned as Venice Mayor on Friday, 13 June. His resignation came one day after he plea-bargained a release from house arrest and accepted a four-month suspended jail term. It is alleged Orsoni took illegal payments towards his 2010 election campaign to be mayor from the consortium in charge of constructing Venice’s mobile dams. According to this report, he faced considerable pressure to resign from the Democratic Party, which had previously backed him and is the party of Prime Minister Matteo Renzi:

Orsoni was suspended from his post on 5 June and was questioned by police on the morning of 6 June. He was elected Mayor in 2010 after a very close election campaign in which he narrowly beat the centre right candidate Renato Brunetta. The arrest of Giovanni Mazzacurati, the former head of the consortium charged with constructing the dams, the Consorzio Venezia Nuova (CVN), in July 2013, led to allegations by Mazzacurati that he took illegal cash payments to the house of Orsoni to help fund the election campaign. In the interview in this newspaper link, Mazzacurati stated that of between €400,000 and €500,000 he provided for Orsoni, only €100,000 was officially recorded:

Orsoni, fondi neri per essere eletto sindaco: sospeso dal prefetto

During the first week of June 2014, Venetian, Italian, and most major international media outlets headlined shocking revelations about financial embezzlement and corruption linked to Venice’s dam project. The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Financial Times and BBC have all run prominent stories about the allegations. On Tuesday, 4 June 2014, Italian police arrested 35 people on accusations of alleged corruption, money laundering and bribery. 10 people were put under house arrest and 25 in jail. Approximately 100 additional people are under investigation, according to judicial sources.

The arrests suggest a wide web of financial irregularities using public funds raised through national taxation to pay for protecting Venice from flooding. Those accused include the former governor of the Venice region, Senator Giancarlo Galan, who was culture minister in 2011 and is now a member of Parliament for the centre right Forza Italia party. As a member of Parliament, Galan is protected by parliamentary immunity from arrest and stands accused pending review by the Upper House of Parliament (Senate). Also arrested was Emilio Spaziante, an ex-general from the Italian finance police, local business people and politicians from across the political spectrum.

Financial corruption linked to the CVN should come as no surprise after the arrest of 14 people, including Mazzacurati, and the placement of a further 100 under investigation in July 2013, as noted in this article:

Ex-head of Venice ‘Moses’ dam project arrested

Indeed, further employees of the CVN were arrested in June 2014. Alarm bells should have been alerting the public to the misuse of funds by the CVN, as the costs of the dam project approximately quadrupled to almost €6 billion, as claimed in this article:

Moreover, the historical circumstances in which the CVN consortium was created, during an era in the 1980s when Italian politics and business were rife with corruption, and the virtual monopoly enjoyed by the consortium should make the recent revelations unsurprising. Indeed, in my book published at the beginning of 2012, this political context and interviews conducted with Venetian activists, explained this problem: Venice in Environmental Peril? Myth and Reality (2012). This is an excerpt from chapter 6 of the book that provides a sample of this political context:

“Through the CVN, companies have enjoyed a virtual monopoly over the design and building of the mobile dams. “So they created a pool of building companies with Fiat first in line, which in the past had a huge role in the Italian economy, because this Project is a great boost for the builders and the Italian economy. So the CVN is a representative for big Italian building companies and their big international interests. It is a way of making money circulate,” claimed Fabrizio Reberschegg (2005)….

In many ways, it is not surprising that the sole concession granted to the CVN was later regarded as an unacceptable monopoly. To understand this claim, it is useful to consider the historical circumstances in which the CVN was established. The CVN was created in a period when the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) dominated Italian politics, holding the offices of President between 1978 and 1985 and Prime Minister between 1983 and 1987. The PSI was characterized by extensive corruption, the awarding of contracts to favored associates, and the use of the state to benefit private interests. From the 1960s, the PSI discarded ideological attachments to socialism, which was replaced by a highly corrupt form of business-orientated politics by the end of the 1980s; “In the absence of any ethical basis to its politics, the PSI attracted and encouraged the ruthless, the ambitious and the unscrupulous. A new category of ‘business politicians’, able at using private resources to build personal support, took over the apparatus at local level,” explains Stephen Gundle (1996, 87). The CVN officially came into being in 1984 when the PSI’s leader Bettino Craxi was Prime Minister. He predicted the mobile dam project would be completed in 1995 as “the first of a new generation of public works” that would place technology at the service of the environment (ANSA 1997). The PSI was the principal victim of the Tangentopoli corruption investigations in the early 1990s; Craxi was convicted for a corruption case from the 1980s and fled into exile in Africa (Gundle 1996, 85-6). Although the legitimacy of such monopolistic bodies as the CVN had been called into question by the 1990s, it was difficult to discard the consortium, as it had overseen the development of the dam project.”

The current scandals in Venice are very much a continuation of the disintegration of Italian politics in the 1980s and 1990s. As politics became less ideological and elites faced less popular pressure from the working-class since the 1970s, many politicians tended to use politics for personal gain, had less in common with each other and were more prone to break ranks and reveal corruption by other politicians, state officials and business people. This is what happened to Craxi in the 1980s and to multiple Italians in the early 1990s. Since Mazzacurati of the CVN and his associates were arrested in July 2013, their testimonies have revealed the web of corruption linked to Venice’s mobile dams. We should expect further revelations as more people give evidence and expose wider corruption.

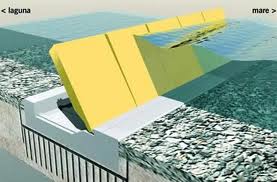

Of course, the corrupt and illegitimate character of the CVN consortium and the misuse of funds by individuals linked to it should be condemned. Nevertheless, this should not detract from the importance of the mobile dam project in terms of its potential to provide vital protection against flooding. The detailed political history about Venice’s protection and the dam project are outlined in my book. Recent developments in the final construction phase of the dam project are described in my recent blog post article:

VENICE’S ‘MOSE’ MOBILE DAMS; FIRST TEST FOR 4 BARRIERS SUCCESSFUL

Even though the project is now mired in corruption and scandal, this final phase should still be completed. To stop the project now would be a huge waste of resources, jeopardise thousands of jobs for people working on the dams and related projects and mean Venice’s capacity for protection against flooding would be significantly diminished. The Italian government needs to ensure that the dam project is completed but without the embezzlement of more funds. Prime Minister Matteo Renzi made a statement on 5 June: “We’ll definitely take action in the next few hours and days on public contracts, anti-corruption (measures) and other specific issues,”. He added that he felt “enormous bitterness” about the corruption probe in Venice and said that he hopes the judiciary hands down sentences “as soon as possible.” These comments were contained in the following article:

Renzi pledges swift action on graft after Venice scandal

Renzi is particularly sensitive about the corruption charges because former Venice Mayor Orsoni is a member of Renzi’s centre-left Democratic Party. An additional problem is that the Venice case is alleged to include some of the same politicians involved in corruption probes two decades ago, which brought down the entire Italian party political system in the early 1990s scandals nicknamed Tangentopoli. According to Venice prosecutor Carlo Nordio, “We’ve found the same suspects from the 1990s”, as discussed in the article in this link:

Venice mayor arrested in flood-system graft scandal

This article also notes that the corruption probe into the dam project is connected to elicit financial dealings investigated for the construction of the A4 highway near Venice. In addition, the embezzlement allegations in Venice come one month after police uncovered a suspected criminal network organising bribes in exchange for contracts for work on Milan’s EXPO world trade fair in 2015. In response, Prime Minister Renzi appointed an anti-corruption czar to look into the Milan scandal. After the recent Venice allegations, Renzi added that politicians convicted of corruption should be given life bans, similar to those imposed on convicted football hooligans. “It’s not possible for someone to be convicted of corruption and then be able to manage public affairs 20 years later,” stated Renzi in this article:

Politicians should be DASPO’d Renzi says on MOSE – update

Renzi might like to reflect upon whether such a ban from political life would also be relevant for his own conviction for wasting €14,000 of taxpayers’ money on four political secretaries. He paid €58.30 extra a month for each of them between 2004 and 2009, which is a small amount of money but he was found guilty. Indeed, the Venice case raises broader questions about democratic legitimacy in Italy. The three leading political figures in Italian politics today are not currently elected as active members of the Italian parliament and all have been found guilty and convicted: Renzi for the misuse of taxpayers’ money, Silvio Berlusconi for tax fraud and Beppe Grillo for manslaughter.

To prevent corruption, Italy needs a change in political culture and the renewal of democratic accountability. In the meantime, important infrastructure innovations like Venice’s mobile dams should proceed with careful checks on funding. It is also vital to sort out who will be the next Mayor of Venice and how the city will be governed. There are many important decisions to take about how to manage the city, especially the pressing question of the passage of cruise ships and their docking in the Venetian lagoon. Protests against cruise ships, the dam project and big project corruption occurred on June 7, 2014.

The national government of ministers announced on 13 June 2014 that the Venice Water Authority would be disbanded from the start of November 2014 with its responsibilities for water-related management to be redistributed to the regional governments of Venice, Friuli Venezia Giulia and Trentino Alto Adige. This was principally because two of the Water Authority former presidents are accused of accepting bribes from the CVN. The city’s budget was scheduled to be set by 31 July 2014. Bold leadership to address these and other issues facing the city will be required by candidates to be the next mayor of Venice, who was planned to become mayor of the wider metropolitan area from 26 June 2014. Elections for a new mayor are unlikely before Spring 2015. In theory, Orsoni has 20 days from his resignation to reconsider, which is unlikely. It seems more likely that the city will be run by a commissioner until elections in Spring 2015.

Comments

2 Responses to “Why have Venice, Italy and the world’s media been stunned by corruption arrests linked to Venice’s MoSE dams and the resignation of Venice Mayor Orsoni?”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...[…] […]

[…] […]